On the way to my first day at Schuyler I had to walk past McCloskey High, and felt a twinge of shame and sadness as I waved and said hello to a number of good friends and former fellow students. It also didn't help that I had to retrace the walk that Father Turner and I had taken just a few days earlier, and probably would have to take every school day from now on. There was some comfort in the fact that I was wearing jeans to school for the first time in my life, though; after all, I had just won my freedom, hadn't I? And wasn't this the first of many rewards? Well, like many things in life, turns out it wasn't necessarily so.

I would soon learn that my tough guy status was not directly transferable to other schools, especially if that school is the end of the line for troubled kids, a place where wiseguys were a dime a dozen. My bargain-basement bravado would soon be tested by barbarians at the school gates; I would be mingling with some of Albany's meanest and baddest boys, and they had no respect for illusions.

Sitting in the same class with legendary figures like Hiawatha White, a gang leader whose feats in battle had earned him his name and elevated him to near-mythical status in the South End, or the Sumo-sized Charlie Smith, who once picked up a manhole cover and caved in a guy's head with it during a fight in front of Sad Sam's Bar on Sheridan Avenue, was enough to take the wind right out of my sails. In English class I would sit next to the leader of a motorcycle gang called The Outlaws who had recently been spotted gnawing a pig's head while sitting on his Harley

in Thatcher Park, and would keep engine parts under his desk. Mongols. Huns. Philistines. I thought wistfully of my run-ins with Father Turner and Sister Marie Frances, but there was no way back.

This might be a good place to point out that in the 1950s, these soon-to-be-lionized characters weren't called 'Greasers'; they were called 'Hoods', a shortened version of 'hoodlum', a term popularized during the Gangster Era in the 1930s. They were the guys who came to school with greased-back hair, wearing denim jeans and a white t-shirt with rolled up sleeves, a red nylon jacket ala James Dean in

Rebel Without a Cause, or motorcycle jacket and boots like Marlon in

The Wild One. They were not universally loved and admired back then, either; they were outcasts, rebels, troublemakers. They weren't nice guys. In fact, they didn't get to date cheerleaders until they were transformed by Hollywood in the 1970s, in movies like

Grease and

The Lords of Flatbush, into cultural heroes.

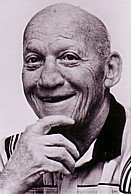

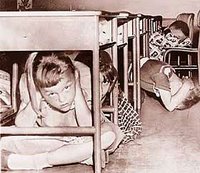

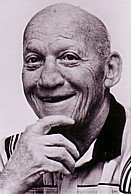

Philip Schuyler did seem a bit strange at first; nearly everyone was on time, teachers were treated with respect, the halls were quiet and orderly... not at all what I expected. Where was the blackboard jungle, where rebellious youth decided things, and we could come and go as we pleased? When I asked the usual suspects while copping a smoke in the boy's room, all I got for an answer was, You'll find out if you ever get sent to the Principal's Office. Now, I had already met Ben Becker, and I could see why you wouldn't want to tangle with him. A former pro boxer who had discovered and trained Sugar Ray Robinson, among others, he parted the hallway

crowds like the Red Sea when he ventured out of his office.

One morning when I walked into my homeroom about 20 minutes late, Mr. Sheehy confronted me about it. I told him just what he could do with himself, and he grabbed my jacket and led me firmly down the hall to the Principal's Office, where I had to cool my heels for at least an hour and build up a good head of steam. Finally the secretary informed me, with an odd look, I thought, that the Principal was ready to see me. Ben Becker sat behind his massive oak desk for a full minute or so, without moving or saying a word. He just sat there looking at me, as though he were psyching me out before the battle began. Then he began to explain what he expected of the students at Philip Schuyler, and when he finished he asked me to tell him what it was that I expected from him. Nothing, I said. Then, silence.

Now the one other crucial bit of information I had learned in the boy's room was that if he began to fold the pinky on his left hand (which apparently didn't work well without boxing gloves on), that I might as well start saying my prayers. Of course, until that moment, I didn't believe a word of it. Besides, I had the role of a tough guy in this movie. Then, well, hell's bells, if he wasn't tucking that little finger in and walking around the desk.

I must have still had a look of complete disbelief on my face when the blow came. I hit the floor like a useless sack of potatoes. The next thing I knew the secretary was giving me a drink of water.

In April, 1967,

Time magazine wrote of Ben Becker's accomplishments at Philip Schuyler High School in a piece entitled

Academy of Hard Cases: "Schuyler is not an ordinary high school, nor is Becker an ordinary principal. Located in Albany's slum-ridden South End, it is an academy for hard cases... many of the students come from broken homes, still others are dropouts from other schools... Becker himself has a broken nose, scar tissue around his eyes—and a brain-jolting jab in his fists. A boy who abuses a teacher will be challenged by his principal to a quiet meeting behind closed doors. The problem is usually solved after Becker flattens the youth with a left cross... No Problem Kids. Backed by the Albany Board of Education, Becker has proved that tough but fair discipline is a remarkable impetus to learning."

I was never sent to his office again. I went on to graduate a few years later, made it out of the slums by joining the Air Force, where I became a Russian linguist in the Intelligence Service, and later a college professor. Many a time I have recalled that day, and tried to calculate how much I owed him. Never could figure that one out, but it must amount to quite a bit. In my senior year,

Ben took a leave of absence to take a group of young men to Rome, Italy, where one of them won a gold medal in boxing. His name was Cassius Clay.

I hear tales to this day of inner city schools that are completely out of control, schools in which teachers are insulted and even physically assaulted by their students, and I think of Ben Becker. Whether it was giving his camel's hair coat to a student who came to school in winter without one, or keeping a closet full of prom dresses for some of the poorer students who might not otherwise be able to attend, Becker influenced an untold number of lives for the better, with his own unique philosophy of tough love and high expectations. Mine, I can proudly say, was one of them. Me, Sugar Ray, and Cassius Clay.

as the primary model for the new building. Begun in 1205 and completed in the 15th Century, its architectural style was early Flemish Gothic. By coincidence, the Cloth Hall at Ypres was destroyed by German artillary fire in November of 1914, shortly after work was begun on its counterpart in Albany.

as the primary model for the new building. Begun in 1205 and completed in the 15th Century, its architectural style was early Flemish Gothic. By coincidence, the Cloth Hall at Ypres was destroyed by German artillary fire in November of 1914, shortly after work was begun on its counterpart in Albany.