Cool On Ice

In the process of writing a piece on skateboarding recently, I found myself at a distinct disadvantage: being much older, I had little or no experience of the world of the skateboarder, a world which may as well have unfolded on another planet as far as I was concerned. In the heyday of street skating, I was living an idyllic life in the suburbs, busy raising three young daughters, each of whom pointedly ignored all the Tonka trucks and bulldozers I bought them, preferring to brush the hair on their Barbies, for some weird reason. It was a girl's world; skateboards did not exist.

Casting about to find a way into the mind of the skateboarder, though, I stumbled upon a most valuable insight: I actually was a skater in my youth: an ice skater. As a young inner city boy, I had pretty much the same attitude and behavior as the dudes of So-Cal who put wheels on their surfboards and hit the ground rolling back in the 70s, later to be known as skateboarders. We had the same lust for thrills, chills and spills, the same yearning to kick ass, and the same mad willingness of the truly immortal to just let it fly, regardless of how many pieces you were in when you landed. Wheels, blades - who cares? It was the need for speed. Kind of a guy thing.

Casting about to find a way into the mind of the skateboarder, though, I stumbled upon a most valuable insight: I actually was a skater in my youth: an ice skater. As a young inner city boy, I had pretty much the same attitude and behavior as the dudes of So-Cal who put wheels on their surfboards and hit the ground rolling back in the 70s, later to be known as skateboarders. We had the same lust for thrills, chills and spills, the same yearning to kick ass, and the same mad willingness of the truly immortal to just let it fly, regardless of how many pieces you were in when you landed. Wheels, blades - who cares? It was the need for speed. Kind of a guy thing.There was this big public park practically in our backyard in Albany; looking at it from the kitchen window of our third floor apartment on Elm Street, it appeared to be one great big bowl scooped out of the center of the city- the flat bottom of which served as a football and baseball field in the summer, then transformed into an ice skating rink in the winter.

This was one big glassy surface, man, at least to a kid; it seemed to be a mile wide, and we made use of every square inch of it, every free minute of the day. At night it was not unusual to have a bonfire going along the edge to rest and warm up and crow about our exploits.

This was one big glassy surface, man, at least to a kid; it seemed to be a mile wide, and we made use of every square inch of it, every free minute of the day. At night it was not unusual to have a bonfire going along the edge to rest and warm up and crow about our exploits.There was no end to the contests we invented, either, to find new thrills, improve our skills, and to polish our manly credentials. Rubber tires were used to create obstacle courses and hurdles, the stack gaining another tire after each contestant succeeded in jumping it. The task was basically to avoid experiencing the feeling of metal blades hitting rubber in midflight with nothing between you and the ice below but a knitted cap; all while exhibiting a sense of style, of course.

There were a number of kids, mostly younger kids and girls, who just skated, doing figure 8s, spins, loops and other things to occupy their time. A few played hockey, but that was not for us. It seemed too boring, and required playing by an elaborate set of rules. If we had enough manpower, we would prefer to play a game of Head On, which consisted of dozens of skaters on two teams, each starting from one side of the field, who, at the cry of HEAD ONNNN! would

launch a high-speed charge across the expanse of ice at one another, the collision in the middle resembling nothing so much as a war scene from Braveheart. As in war, the last one standing was the winner.

launch a high-speed charge across the expanse of ice at one another, the collision in the middle resembling nothing so much as a war scene from Braveheart. As in war, the last one standing was the winner.But to give you some idea of the true scope of our madness, I will tell you a tale of unmatched bravery, with a bit of bravado, a touch of humor, a pinch of stupidity, and a whole lot of pain.

We awoke one morning to the dazzling sight of a historic ice storm in the city, back in the days when winter could still be expected to behave like winter, and such things were extremely rare. Trees were down, the power was out, the city had been brought to a standstill. Most miraculously, the schools were closed. Bob and I, of course, immediately realized the full potential of the moment, the magical gift we had been given: the entire town had been turned into a skating rink!!! We quickly grabbed our skates and ran out the door to round up some of our skating buddies.

While cruising through the empty streets, we soon recognized a simple but heretofore unrealized fact that, unlike the surface of a skating rink, many streets in our neighborhood sloped down toward the Hudson River, and you could actually ski down them. In fact, someone suggested, if you could find the right streets, you could . . actually . . fly.

I don't recall who thought of it first, but suddenly we all looked at one another in a state of electric ecstasy: lying right behind us were the numerous sidewalks of Lincoln Park, many running straight down hill and ending at the icy lake at the bottom. Jesus, Mary and Joseph. What the hell are we waiting for?

I don't recall who thought of it first, but suddenly we all looked at one another in a state of electric ecstasy: lying right behind us were the numerous sidewalks of Lincoln Park, many running straight down hill and ending at the icy lake at the bottom. Jesus, Mary and Joseph. What the hell are we waiting for?We soon found ourselves flying at speeds only dreamed of by other skaters of the world; we were downhill racers with nothing beneath us but metal and ice, crouched for minimum wind resistance, well on our way to establishing new land speed records. But the records were never to be recorded, and are now lost to history. Besides, even if we had succeeded, we ourselves would later smash it more than a decade later, as Bob so beautifully chronicles in his recent post, The Right Stuff. Little did it matter if we did this in a vacuum, though; it was really about the adrenaline. The intoxicating thrill of speed and, oh yeah, the danger.

After each successful run and subsequent laborious return to the top of the hill, we would choose to see who went first. The lead-off run would then set a speed and distance for the rest of us to try to measure up to, and hopefully surpass. On what would turn out to be our last run, Larry won the first slot. He set off tightly coiled down a particularly steep and curvy piece of crystallized concrete.

Trouble started about halfway down the hill, though, when his blade hit a crack in the ice, setting him off balance for a split second. That split second sealed his fate.

Trouble started about halfway down the hill, though, when his blade hit a crack in the ice, setting him off balance for a split second. That split second sealed his fate.As he struggled to correct this problem, his skates went out from under him, he hit the ice-coated surface hard, and now found himself flying down the hill in a sitting position, with very little to slow him but the blades of his skates. But it was too late. We knew something was horribly wrong when we heard the scream, a sound like nothing we had ever heard coming from his lips, as he continued to hurtle down the hill. We all instantly set off after him, now a mountain rescue team, to learn what had happened, and tend to our fallen comrade.

Midway down that hill, some anonymous saboteur had thoughtlessly shattered a soda bottle on the sidewalk, just for kicks, I would assume, being somewhat familiar with the phenomenon. Pieces of it were still lying on the concrete when the storm hit, and were now frozen solid to the ground; embedded knives fixed in place as though by Satan, ready to yield maximum pain to its first unsuspecting victim. One particular piece is still seared (frozen?) into my memory: the bottom of the bottle, base down, with several jagged, razor-sharp mountain peaks jutting out of the surface of the ice. Larry hit that thing doing at least forty miles an hour, with nothing to protect him but a pair of well-worn Levi jeans. They may be tough, but they ain't that tough.

Hours later, as we all sat around the hospital waiting room waiting for him to be stitched back together, we couldn't help but crack a few jokes about the event, as boys will. It's an ancient coping mechanism, I believe; probably having helped many a caveboy to get through the night after a particularly bad encounter with a mastodon or sabre-toothed tiger.

A number of jokes involved various body parts, as I recall, and what may or may not have become of Larry had he hit the glass just an inch or two in either direction, but I won't go into those details here. Suffice it to say that Larry is living happily ever after, married, with children. 'Nuff said.

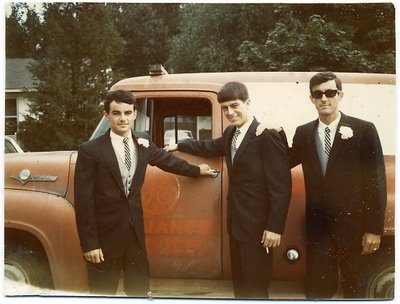

A number of jokes involved various body parts, as I recall, and what may or may not have become of Larry had he hit the glass just an inch or two in either direction, but I won't go into those details here. Suffice it to say that Larry is living happily ever after, married, with children. 'Nuff said.Afterthought: All of this, I suppose, was written by the inner boy that dwells within an aging man; a man grateful to this day that he survived the antics of the boy's days of glory, long since past. If you listen real close, though, you can still hear the little guy jumping up and down, shouting, Hey, all you California skating dudes, them skateboards ain't nothin' when the only price you got to pay for a mistake is a few scrapes and bruises and maybe a broken bone or two. You ain't done a goddam thing 'til you come to New York and break the land speed record on a mountain of glass, and pay the full price with half your ass.

Ok, that's it. I've had just about enough! Go over there, sit down and be quiet. I don't want to hear another sound out of you. See, he just hasn't learned yet what the aging man has long since learned: that you can't be immortal forever.